Harris is one of eight candidates on the Classic Baseball Era Committee ballot for the Hall of Fame. A 16-member committee, filled with Hall of Famers, historians, media members, and baseball executives, will meet next Sunday at baseball’s winter meetings in San Diego to consider the candidacies of Harris and seven others. The other candidates are Dick Allen, Dave Parker, Steve Garvey, Ken Boyer, Luis Tiant, Tommy John, and John Donaldson, a pitching legend of the Negro Leagues.

The 16 voting members on the Classic Baseball Committee can vote for a maximum of three out of eight players. To get a plaque in Cooperstown, a candidate must get 12 out of 16 votes (75%).

Harris and Donaldson were on the “Early Baseball” ballot three years ago; Negro League pioneers Buck O’Neil and Bud Fowler were elected to the Hall of Fame’s Class of 2022, while Harris fell just two votes short of Cooperstown, getting 10 out of 16.

Besides his record as a skipper, Harris was also an excellent player, mostly as a left fielder. A left-handed spray hitter, he earned the nickname “Vicious Vic” for his reputation for violent behavior, both on and off the field. He was an aggressive baserunner known for his hustle. According to veteran second baseman Dick Seay, “he would cut you in a minute. Cut you and laugh.”

“Considered by many to be a dirty ballplayer, on another occasion, while engaged in an argument with an umpire, he spit in the arbiter’s face… In many ways his behavior toward umpires was in contrast to the generally quiet approach he used with his players, never saying too much and preferring to inspire them by example to give their maximum effort. Although he was not noted s as a brilliant strategist, the players responded to the fiery manger by giving good performances on the baseball diamond.”

— James A. Riley, The Biographical Enclyopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (1994)

According to the Seamheads Negro Leagues database, Harris hit .305 in 25 seasons as a player.

With the major caveat that comparing Harris (or Donaldson) to the other players (all from the 1960s through the 1980s) is an exceedingly difficult task, in this piece, I’ll make the case for and against Harris for Cooperstown.

Cooperstown Cred: Vic Harris

- As a player (25 seasons): Pittsburgh Keystones (1922), Cleveland Tate Stars (1923), Cleveland Browns (1924), Chicago American Giants (1924), Homestead Grays (1925-33, 1935-45), Detroit Wolves (1932), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1934)

- Managed the Homestead Grays from 1936-42 and 1945-48

- Career as manager: 547-278 (.663)

- As a manager: 269 games over .500 are the 23rd most in Major League Baseball History, behind 18 Hall of Famers, Dave Roberts, Dusty Baker, Davey Johnson, and Terry Francona.

- As a manager: .663 WL% is the highest in baseball history (minimum 500 games managed)

- Led the Homestead Grays to seven Negro National League pennants

- Won the 1948 Negro League World Series over the Birmingham Black Barons

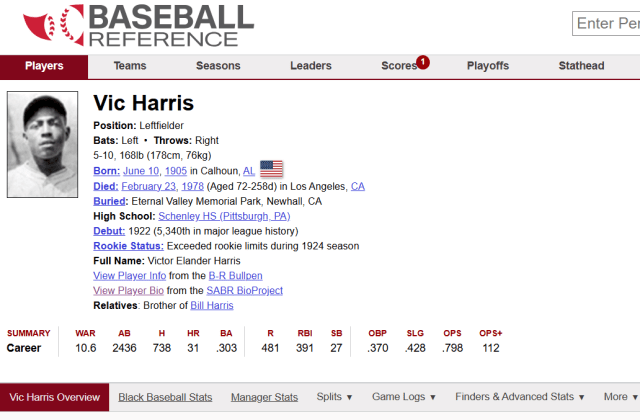

- As a player: .303 BA, .370 OBP, .428 SLG, 112 OPS+ (per Baseball Reference)

- 6-time All-Star as a player

Vic Harris Career Highlights

Victor Elander Harris was born on June 10, 1905, in Pensacola, Florida, to William and Frances Harris. Two of Vic’s brothers (Bill and Neal) also played in the Negro Leagues. The Harris family moved to the Pittsburgh area when Vic was nine or ten years old.

Vic Harris began his professional baseball career in 1922 with the Pittsburgh Keystones. He played for three different teams in Cleveland and Chicago in 1923-24, playing for future Hall of Fame manager/pioneer Rube Foster with the Chicago American Giants.

Harris came home to the Pittsburgh area, signing with Cumberland Posey, the owner of the Homestead Grays and a future Hall of Famer as a pioneer. Harris would spend virtually the rest of his baseball playing and managing career with the Grays. The Grays were an independent team in Harris’s early years with the squad; box scores from 1925-27 are scarce. Posey named Harris the captain of the team in 1928, a season in which he hit .333 in 107 recorded plate appearances (according to Seamheads).

The Grays joined the new American Negro League in 1929. Baseball-Reference credits Harris with a .296 BA and 40 RBI in 291 PA. The American Negro League lasted only that one season; in 1930, with the Great Depression wreaking havoc upon the nation, the Grays became an independent team again. This was a powerhouse squad featuring future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, and Smokey Joe Williams, who earned 11 of the Grays’ 44 wins at the age of 44.

Seamheads credits Harris with a slash line of .359/.424/.576 (145 OPS+) on the 1930 Grays. The Grays beat the Lincoln Giants six games to three in a series for the title of “Colored Champions of the East.”

The 1931 Grays are regarded as one of the greatest teams in baseball. Besides Gibson, Charleston, and Williams, the ’31 edition featured two more future Hall of Famers, third baseman Jud Wilson and pitcher Bill Foster. Researcher Phil Dixon estimated that the Grays played 174 total games, winning 143 of them for a whopping .822 winning percentage. Seamheads credits Harris with only a .279 average in 37 games; Dixon estimated that Harris actually hit .403.

In 1932, Harris started the season playing for the Detroit Wolves. Harris’s teammates in Detroit included future Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell, Mule Suttles, and Willie Wells. The Wolves folded in the middle of the season, so Harris returned to the Grays.

In 1933, Harris was an All-Star in the first East-West All-Star Game and, in balloting conducted by the Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender, he got the second most votes for the contest (behind only Hall of Famer Turkey Stearnes).

For the 1934 campaign, Harris played for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, rejoining Gibson and Charleston, who had been poached a few years earlier. Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, and 27-year-old Satchel Paige were also on the Crawfords. Harris was an All-Star again, hitting .335 (129 OPS+), according to Baseball-Reference.

Player-Manager Vic Harris

Vic Harris returned to the Homestead Grays in 1935, with Posey making him the team’s manager (although Posey is still listed as the skipper for the ’35 edition of the team). The Grays went only 26-32 in ’35, which does help Harris’s career managerial record because Posey was listed at the helm.

Both Baseball Reference and Seamheads list Harris as the team’s manager in 1936, when the Grays went 31-27-1. On the field, Harris hit .355 (with a .414 OBP). Two Hall of Famers were on the ”35-’36 Grays: first baseman Buck Leonard and pitcher Ray Brown.

For the 1937 campaign, Posey was able to lure Gibson back to the Grays. Gibson had a monster year, slashing .417/.500/.974 with 20 HR and 73 RBI in just 39 games for which his box scores have been found. Harris also had a big year with the bat, hitting .327 (142 OPS+) with 17 doubles and 48 RBI, both career bests. The Grays went 45-18-1 in the Negro National League (60-19-1 overall). The Grays won the first of what would be nine straight NNL pennants (sort of, see below).

The Grays went 56-14 in 1938, with Harris being named to his third All-Star squad as a player (he hit .297 for the season). Leonard had a ridiculous slash line (.420/.500/.740), while Gibson slashed a mere .370/.467/.721 while leading the league with 13 HR and 54 RBI. Brown had a big year on the mound, going 14-0 with a 1.88 ERA.

In 1939, Harris slumped to a .264 BA (though he was still an All-Star). The Grays won the pennant again (38-21-1), with Gibson and Leonard leading the way. As Jay Jaffe noted in his piece about Harris, for some reason, Baseball-Reference and Seamheads don’t list the Grays as the pennant winners in ’39, but other sources do.

Beginning in 1940, the Grays started splitting time between Forbes Field in Pittsburgh and Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC.

The 1940 Grays went 42-20 (Harris hit .273 with a 93 OPS+) for another pennant. 44-year-old Jud Wilson returned to the Grays at third base. Brown went 17-2 with a 2.07 ERA, while Leonard slashed .378/.491/.638. Meanwhile, Gibson spent most of the 1940 campaign playing in Mexico.

Gibson was still in Mexico, but Leonard and the rest of the Grays still 51-24-2 in 1941 to win the pennant yet again. Harris, now in his age-36 season as a player, hit just .233 with a lowly 71 OPS+. Harris was named manager of the East-West Classic for the first time (and would have the honor in five additional seasons).

Gibson returned to the Grays in 1942, leading the squad to a 64-23-3 record and another pennant. Harris hit .264 with a 97 OPS+.

Harris remained with the Grays in 1943 but took a leave of absence as the team’s manager so that he could take a job at a defense plant. He still appeared in home games and had a renaissance season with the bat, hitting .358 (122 OPS+) in 153 PA.

Candy Jim Taylor, who had a 30-year career as a skipper in the Negro Leagues, took over the reins as manager. Gibson had the best season of his career, slashing .466/.560/.867 with 20 HR and 109 RBI (in just 69 games). Cool Papa Bell rejoined the Grays in his age-40 season.

The Grays, under Taylor, won the pennant again in 1944. Harris only appeared in 19 games and hit .444. The Grays defeated the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro League World Series in both 1943 and ’44.

Harris returned to the dugout for the 1945 campaign, leading the Grays to a 47-26-3 record and another pennant. In what would be his final season as a player, Harris hit .233 (with a lowly 45 OPS+). In the postseason, the Grays were swept in the World Series by the Cleveland Buckeyes, with the Buckeyes’ pitching holding Gibson, Leonard, and Bell to a combined .186 BA.

After nine straight pennants, the 1946 Homestead Grays went just 45-38-3 to finish 3rd in the NNL. The big three bats continued to hit like Hall of Famers, but the Grays’ pitching posted a lowly 4.51 ERA. Gibson shockingly died of a stroke in January 1947; without their biggest star, the Grays under Harris still went 57-42-4 (although 22 of those wins were in non-league games, so the team finished 4th in the NNL).

The National League and American League started to integrate in 1947, with Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby crossing the color line. As a result, the Negro Leagues would not last much longer. In 1948, in what was his final season as the team’s manager, Harris led the Grays to a 56-24-2 record and another pennant. To put an exclamation point at the end of a great managerial career, the Grays defeated the Baltimore Elite Giants in the NN2 Championship Series and the Birmingham Black Barons in the World Series.

The NNL was disbanded after the 1948 season. The Grays became a member of the Negro American Association, a black minor league, in 1949. Harris signed on as a coach with the Elite Giants in 1949 and managed the Black Barons in 1950 (to a 52-25 record). He retired from professional baseball after the 1950 campaign at just 45 years old.

In his retirement, Harris was the head custodian for the Castaic Union Schools in Castaic, California. He died on February 23, 1978, at age 72, from cancer.

The Hall of Fame Case for Vic Harris

There are 345 men (and one woman) who are enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown. Out of those 346 enshrinees, 37 are primarily associated with the Negro Leagues. The list does not include stars such as Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and others, who got their start in the Negro Leagues but are Hall of Famers due to their deeds in the American and National Leagues.

The list of 346 Hall of Famers includes 23 men inducted as managers. All 23 of those managers managed in the American or National Leagues. There are no Hall of Fame managers from the Negro Leagues. There are eight Negro League pioneers or executives in Cooperstown (including Cumberland Posey) but no skippers.

So, if Vic Harris can be credibly called the greatest manager in the history of the Negro Leagues, that makes him a pretty obvious pick for the Hall of Fame. Add in, for good measure, that he was an excellent defensive left fielder and a .303 hitter.

Additionally, some of his contemporary players and prominent historians argue that Harris is worthy of Cooperstown based on his playing credentials alone.

“Negro League veterans Larry Doby and Double Duty Radcliffe are among many who have opined that Harris should in the Hall of Fame solely on his accomplishements as an outfielder. Leading historians John B. Howay, Larry Lester, Phil S. Dixon and Jay Sanford have similarly concluded that Harris is a Hall of Fame qualified as a left fielder alone.”

— Steven Greenes, Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame

“The most undererated ball player I’ve known was Vic Harris. Every time I saw him, he played a heck of a game, offensively and defensively. Left-handed hitter, he’d spray the ball, hit it over here, hit it over there. Day in dayout, year in year out.”

— Willie Foster, Hall of Fame pitcher.

All of the players and historians listed above are (or were) in a far better position to evaluate Harris’s playing career than I am, but it is a truism that there are hundreds of players not enshrined in Cooperstown who have advocates on their behalf. Just looking at the historical record, I don’t see a Harris as a Hall of Famer on the diamond.

So, I will focus his Hall of Fame case on his success in the dugout.

The Challenge of Sorting through the Records

First of all, the same limitations that we have on any Negro Leaguers playing record comes into play with respect to managers. The statistical record is incomplete, and the schedules of the several different leagues varied widely. In the traditional Major Leagues (the American and National Leagues), teams played 154 games per year until 1961 in the A.L. and 1962 in the N.L., when the leagues expanded to 162 games.

Gary Ashwill, the founder and lead researcher of the Seamheads Negro Leagues database, explains what we can see on Baseball Reference’s main leaderboard pages:

“One thing you will find is that the statistics here show Negro League teams with fewer regular season games than the contemporary White major leagues, usually 50-100 compared to the standard 154 games in the National League and American League at the time. This is not because they actually played fewer games (in fact, as we’ll see below, much of the time they played more). It’s because Black baseball teams, in the days of segregation, played a more complex schedule than White major league teams, and league games formed only a part of their season—a very important part, but only a part….

Negro Leaguers played games against independent Black teams, interleague games against teams in the other Black major league, exhibition games against White major & minor leaguers, and many, many games against White semipro & amateur teams. Altogether a Negro League team might play as many as 150-200 games a year, with only a quarter to half being league games, depending on the season.”

— Gary Ashwill, Baseball-Reference

In 2020, Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred announced that the Negro Leagues would be officially elevated to Major League status. However, not all games played by Negro Leaguers are included. On Baseball Reference, statistics from seven recognized leagues are included on the main pages and the Stathead “Play Index” leaderboards but the non-league games are not.

You can see that, just to the right of “Vic Harris Overview” are “Black Baseball Stats.” Those statistics include seasons in which the Homestead Grays were an independent team and not one of the seven recognized “Major Leagues.”

You can tell the difference between the two by the designation “Maj” (for official Major Leagues) or “Non” (for seasons that were not).

Why am I going through this history lesson about Vic Harris’s playing statistics when I’ve already declared that I’m going to focus his case for Cooperstown on his managerial exploits? The reason is to explain that there are also two sets of managerial statistics for Negro League managers. One of them includes only the seven recognized Major Leagues (this is what you see in “Manager Stats” on Baseball Reference); the other is on Seamheads, which includes non-league games. Even that record, however, remains incomplete.

This does make it difficult to fairly evaluate all skippers in black baseball. But we work with what we can and will do our best.

The Vic Harris Managerial Record

Let’s start by sharing the Manager page for Vic Harris on Baseball Reference.

Next, let’s compare Harris to other top skippers from the Negro Leagues. On this first list, I’m sharing the managerial records of seven Negro League skippers from the seven recognized leagues. These records can be found on each man’s individual page as well as on the Manager Index, where they’re included with all Major League managers.

| Manager | Years | W | L | WL% | G>.500 | Penn | WS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candy Jim Taylor | 27 | 955 | 991 | .491 | -36 | 3 | 2 |

| Vic Harris | 12 | 547 | 278 | .663 | 269 | 7 | 1 |

| Oscar Charleston | 14 | 420 | 377 | .527 | 43 | 3 | 0 |

| Rube Foster | 7 | 336 | 195 | .633 | 141 | 3 | 0 |

| Dick Lundy | 11 | 303 | 259 | .539 | 44 | 2 | 0 |

| Dave Malarcher | 7 | 263 | 56 | .628 | 107 | 3 | 2 |

| Bullet Rogan | 5 | 257 | 111 | .698 | 146 | 1 | 0 |

As you can see, on this list, only the legendary Candy Jim Taylor, who replaced Harris in the Grays’ dugout in 1943 and ’44, won more games in the seven recognized Major Leagues. Taylor could be credibly called the Connie Mack of the Negro Leagues (Mack managed 7,755 MLB games, winning 3,731 of them in a 53-season career).

On this list, there are three men who are already in the Hall of Fame. Rube Foster is widely known as the “father of the Negro Leagues,” while Oscar Charleston and Bullet Rogan are in the Hall because of their excellence on the field as players.

Anyway, Vic Harris’s record is unmatched on this list. His seven pennants (not including the eighth, from 1939, that’s strangely not counted) are vastly more than any other skipper on the list. His winning percentage is second best (to Rogan), but he managed in many more games.

Now, as I mentioned, the Baseball Reference managerial database only includes games in the seven recognized Major Leagues. This next list, from Seamheads, includes non-Major League games.

| Manager | Years | W | L | WL% | G>.500 | Penn | WS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candy Jim Taylor | 30 | 1091 | 1160 | .485 | -69 | 3 | 2 |

| Tinti Molina | 27 | 758 | 908 | .455 | -150 | 4 | 0 |

| Rube Foster | 20 | 746 | 420 | .640 | 326 | 4 | 0 |

| Vic Harris | 12 | 639 | 322 | .665 | 317 | 7 | 1 |

| Oscar Charleston | 15 | 494 | 437 | .531 | 20 | 2 | 0 |

| John Henry Lloyd | 18 | 443 | 379 | .539 | 64 | 1 | 0 |

| Frank Duncan | 6 | 353 | 274 | .563 | 79 | 2 | 1 |

| Dick Lundy | 13 | 352 | 298 | .542 | 54 | 2 | 0 |

On this list, it’s a coin flip about whether Harris or Foster could be creditably called the best manager in the history of the Negro Leagues. However, Foster is already in the Hall of Fame, so it’s a moot point. Plus, the second list includes 410 wins for Foster in the non-Major League versions of the Negro Leagues.

To use a recent example as a point of comparison to Foster, Jim Leyland was elected to the Hall of Fame this summer on the strength of his 1,769 wins (and three pennants) in 22 MLB campaigns. Leyland also won 730 games in the minor leagues (in 11 seasons), but that’s not part of the record on his plaque in Cooperstown.

Vic Harris vs. Other Hall of Fame Managers

As previously noted, there are 23 men in the Hall of Fame who were elected as managers. All 23 managers were players at earlier times in their lives, with varying degrees of success. All 23 are white.

If Vic Harris gets the nod next Sunday and is elected to the Hall of Fame, he will have one of the three strongest playing resumes among the skippers enshrined in Cooperstown. The best player among the 23 skippers was unquestionably Joe Torre, who was a .297 hitter as primarily a catcher, was a nine-time All-Star, won an MVP Award, and earned a 57.6 career WAR (according to Baseball-Reference).

John McGraw won ten pennants and three World Series titles with the New York Giants, with two pennants (one World Series) coming as a player-manager. As a player, McGraw was a .334 career hitter, with modern sabermetrics crediting him with a 45.7 WAR and a 133 OPS+ in just 4,946 career plate appearances.

Like Harris, McGraw was a hard-nosed player, a spray hitter, and an aggressive baserunner known for hard slides and fights with umpires. McGraw was known as Little Napoleon; Harris was Vicious Vic.

McGraw is an inner circle Hall of Famer as a manager, one who finished with a 2,763-1,948 record (.586), winning a whopping 815 more games than he lost. How could one even start to compare McGraw to Harris as managers, given that McGraw managed 4,769 games in 33 seasons, compared to Harris’s 845 Major League games (in 11 seasons)? It’s apples to bowling balls, of course, but think about this.

- At the end of the 1916 season, when McGraw was 43 years old, he was 1,501-1,025 (.594) in 18 managerial campaigns. He had won four pennants and one World Series title.

- At the end of the 1948 season, when Harris was 43 years old, he was 547-278 (.663) in 11 managerial campaigns. He had won seven pennants and one Negro League World Series title.

Aside from the raw totals of games managed, there’s not much difference there. Of course, McGraw would go on to manage for 15 more seasons, while Harris’s managerial career was over with the demise of the Negro Leagues, and he became a custodian. While the original Major Leagues were integrating on the diamond, it would be decades before a black man would be hired as a manager (Frank Robinson in 1975).

Of course, you don’t have to equate Harris to McGraw to make the Hall of Fame case for Harris. It’s just like players who make the Hall of Fame don’t have to compare favorably to Babe Ruth or Willie Mays.

Vic Harris’ Won-Loss Record and Games Above .500

As we remember, once again, that not every game Vic Harris managed is counted on the Baseball Reference database, he still compares remarkably well to other Hall of Fame skippers when looking at how his teams dominated their competition.

This is the list of managers who skippered at least 500 Major League Baseball games, ranked by won-loss record (WL%).

| Manager | Years | W | L | WL% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vic Harris | 11 | 547 | 278 | .663 |

| *Rube Foster | 7 | 336 | 195 | .633 |

| Dave Roberts | 10 | 851 | 507 | .627 |

| *Joe McCarthy | 24 | 2125 | 1333 | .615 |

| Jim Mutrie | 9 | 658 | 419 | .611 |

| *Charlie Comiskey | 12 | 839 | 540 | .608 |

| *Frank Selee | 16 | 1284 | 862 | .598 |

| *Billy Southworth | 13 | 1044 | 704 | .597 |

| *Frank Chance | 11 | 946 | 648 | .593 |

| *John McGraw | 33 | 2763 | 1948 | .586 |

| *Hall of Famer |

Harris is number one on the list. All but two of the other names are either in the Hall of Fame as a pioneer (Charles Comiskey and Rube Foster), player (Frank Chance), or manager (Joe McCarthy, Frank Selee, Billy Southworth, and John McGraw). The men not in the Hall are Dave Roberts, who is still active, and Jim Mutrie, who managed the Giants in the 19th century.

While it’s true that Harris had the good fortune of managing Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, nobody holds it against McCarthy that he managed Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Joe DiMaggio.

Additionally, as noted at the top of the piece, Harris finished with 269 more managerial wins than losses; that’s the 23rd most games above .500 among all MLB managers in history. He’s behind 18 Hall of Fame managers, plus Roberts, Dusty Baker, Davey Johnson, and Terry Francona. Among those men, Baker feels like a virtual lock to be elected when he’s eligible in two years. Francona also feels like a sure thing.

If one were to give Harris “double credit” because he managed less than half the games per year as the others on the list, he would be behind only McGraw and McCarthy.

The Bill James Managerial Points System

Over a decade ago, on Bill James Online (which is no longer in service), sabermetric pioneer Bill James wrote a series of articles in which he attempted to create a formula to evaluate managers: the formula was based on wins, wins above .500, pennants and titles won, and exceeding expectations (which took a look back a team’s previous two seasons).

Here’s how it works:

- One point for every 40 wins

- One point for every ten games above .500

- Three points for a Division Championship, three more for a pennant (6 total), and three more for a World Championship (9 total)

- For an individual season, one point for every five games a team exceeds expectations (see my piece about Baker for details on how this works)

James created the formula with the expectation that 100 on the scale indicated a Hall of Fame-worthy career for an MLB skipper.

Since 2008, there have been seven managers elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans or Era Committees with the points that they earned on the Bill James system:

- Billy Southworth (2008): 102 points

- Dick Williams (2008): 97

- Whitey Herzog (2010): 88

- Bobby Cox (2014): 206

- Tony La Russa (2014): 196

- Joe Torre (2014): 177

- Jim Leyland (2024): 102

When you look at the eleven seasons in the dugout for Vic Harris, he gets 13.7 points for winning 547 games, 26.9 points for being 269 games over .500, 15.4 points for “exceeding expectations,” 21 points for winning seven pennants, and three more for his World Series title.

That makes his total 80. Although that’s lower than the recently enshrined managers, it’s still in range, which is all the more remarkable given that he was limited to an average of 75 games per season and that his managerial career was short-circuited by the end of the Negro Leagues and the lack of Major League opportunities.

When it comes to the Hall of Fame candidacies as players, I’ve long believed that it’s appropriate to give credit and deference for time missed to military service, the color line, or player strikes. When it comes to his tenure as a manager, Harris lost time due to both the lack of opportunities for a black manager in the American and National Leagues, and he also took two years off from managing to take a job that supported the nation’s war effort in World War II.

If Harris had remained the manager for the 1943 and ’44 Homestead Grays (and the same outcomes occurred), his Bill James point total would have been over 100.

Conclusion

Having gone through the comparisons in the previous sections, it’s a pretty obvious call to me that Vic Harris deserves a plaque in the Hall of Fame. One of the few writers who has spilled more proverbial ink about the Hall of Fame than I have agrees:

“If Harris were simply considered on his merits as a player, they might not be enough, though the list of historians who believe he’s worthy on that basis alone (Phil Dixon, John Holway, Larry Lester)…. Putting that aside, it’s Harris’ unparalleled success as a manager in the major Negro Leagues that’s his real selling point; as noted, he won more pennants than any other such manager, and even without counting 1939 as one of them, it’s not close. Charleston, Taylor, Andy Cooper, Rube Foster, Dave Malarcher, Jose Mendéz, and Frank Warfield are tied with the next-highest total of three… If anyone were going to elect a manager based upon what he did during the 1920-48 period in the major Negro Leagues, I don’t see how the line starts with anybody but Harris. Leading historians, including Riley and Holway, designated him as a manager on their all-time teams.”

— Jay Jaffe, FanGraphs (December 1, 2024)

That leads to the next question. Is Harris one of the best three candidates on the Classic Baseball ballot? As noted at the top of the piece, there are eight total candidates; the 16 members of the committee can vote for a maximum of three out of eight. It’s hard math, requiring a candidate to get 12 out of 16 votes (75%) for enshrinement.

The other candidate from the Negro Leagues is left-handed pitcher John Donaldson, who allegedly (according to the Donaldson network) won 428 games with 5,295 strikeouts, 14 no-hitters, and two perfect games in 33 years. That sounds pretty amazing, right? The problem is that the vast majority of those games were pitched against inferior competition. Donaldson pitched only 22 games that are in the Negro Leagues which are designated as the Major Leagues. Even the Seamheads database shows only 61 games pitched (with a 23-25 record).

Jaffe, quoting historian James A. Riley, noted that Donaldson spent his prime “playing against white semi-pro ballclubs of dubious quality, resulting in both inflated statistics and fragmentary records.”

Anyway, it’s hard to compare Donaldson directly to Harris. If I had to choose between the two, I’d vote for Harris. He would be the first Negro Leagues manager, the first black manager, and the record is clear, while Donaldson’s record is harder to assess due to the quality of competition.

Of course, the voters on the Classic Baseball committee could vote for both Harris and Donaldson, but I doubt that they will. My guess is that most of the voters are going to create two buckets of candidates, one with Donaldson and Harris, and the other with the six players from the 1960s through 1980s (Tommy John, Luis Tiant, Dick Allen, Ken Boyer, Steve Garvey, and Dave Parker).

It’s usually a fool’s errand to predict who the 16 committee members will vote for, but I think that Vic Harris is going to make it to the Hall of Fame next Sunday. Three years ago, he got 10 out of 16 votes (losing out to Negro League pioneers Buck O’Neil and Bud Fowler). He and Allen (11 votes on two previous ballots) have the best track record on recent Era Committee ballots.

The committee members will be different this time, but the Vic Harris case for Cooperstown is the easiest to crystallize into a phrase: winningest manager in the history of the Negro Leagues. Simple. Easy to understand and will make him a Hall of Famer.

Thanks for reading.

Please follow Cooperstown Cred on X at @cooperstowncred or on BlueSky @cooperstowncred.bsky.social.

I’d say “YES” to inducting Harris. BTW, is McGraw 2nd in WAR among HOF managers?

Of course the Hall screwed him this year, the Hall failed the voters (who are publicly available to know who they are but not how they voted), the voters failed Harris