It was the first time since 2001 that what used to be called the Veterans Committee has elected a living former player and it was the first time since 1975 that they actually elected two. After the BBWAA (Baseball Writers Association of America) voted in four more candidates in January (Chipper Jones, Jim Thome, Trevor Hoffman, Vladimir Guerrero), Cooperstown celebrated its biggest Hall of Fame class of living ex-players since 1955, when Joe DiMaggio, Gabby Hartnett, Ray Schalk, Home Run Baker, Dazzy Vance, and Ted Lyons all were granted plaques in the Hall.

The Veterans Committees (now known as the Eras Committees) are designed to give a 2nd chance to players who were not recognized by the writers. Morris came very close to being inducted by the BBWAA, maxing out at 67.5% of the vote in 2013 before falling back to 61.5% in the final of his 15 years on the ballot in 2014.

The Modern Baseball Committee that voted on Morris, Trammell, and eight other candidates contained eight Hall of Famers (George Brett, Rod Carew, Bobby Cox, Dennis Eckersley, John Schuerholz, Don Sutton, Dave Winfield, and Robin Yount) along with five executives and three longtime media members. It’s notable that all eight Hall of Famers either played against, managed against, or “general managed” against both Morris and Trammell.

The body of this piece is to make the case that Jack Morris fully earned his Hall of Fame plaque with his performance on the mound. This is not just a story about “old school” players ignoring modern analytics. Although his epic 10-inning shutout in Game 7 of the 1991 World Series might very well have been the tie-breaker that put him in the Hall of Fame, his career was about so much more than that one game.

The detractors of Morris’ candidacy have always pointed to his low WAR (43.8) and his high ERA. At 3.90, his ERA is the highest of any inducted starting pitcher.

The panel (the Modern Baseball Committee), with a median age well above 60, was always more likely to be sympathetic to Morris’s old-school charms than the stat-savvy BBWAA minority that kept him out… That Morris, who understandably expressed some bitterness at the BBWAA outcome, gets some peace is a positive. He didn’t ask to become a battlefront in a cultural war that’s largely been won, as analytics has permeated every front office in baseball, and subsequent elections, such as those of Jeff Bagwell and Tim Raines last year, have solidified the incorporation of advanced statistics into Hall of Fame debates. Still, his election lowers the bar for Hall of Fame pitchers.

— Jay Jaffe, si.com (December 10, 2017)

One of the members of the Modern Game Committee was Jayson Stark, a long-time writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer and espn.com. In an interview the day after the election on MLB Network, Stark acknowledged that there were people who were “unhappy” with who was elected (referring to the sabermetric community and its anti-Morris bent). But he also insisted that it wasn’t just a room full of people ignoring statistics.

There were people in the room who were willing to look past ERA and could see 14 Opening Day starts in a row, and could see 3 different starts in an All-Star game for three different managers, who could look at a guy who pitched in seven post-season series and started Game 1 in six of them. They looked at the innings differential between Jack Morris in his prime and everyone else… It’s obvious that there were many people who valued that, who think that an ace is someone who takes the ball, wants the ball in the biggest situations and doesn’t want to give it up.

— Jayson Stark (on MLB Network, December 11, 2017)

For the record, Stark referenced the innings pitched. Morris logged 511 more innings (from 1979-92) than any other pitcher.

You will, in this piece, read some arguments and see some statistics in favor of Morris as a worthy Hall of Famer that you have never seen before (put in boldface deliberately to excite, tantalize or disgust you). This will include a sabermetric argument in favor of Morris’ induction into the Hall.

This piece represents a comprehensive analysis so it’s a little bit long. If you care about the topic, it’s worth the read. If you’re marginally interested, there are headlines along the way to help steer you to the parts you’re most curious about. If you’re a sabermetrically inclined reader and short on time, don’t miss the section about the sabermetric case for Morris.

Cooperstown Cred: Jack Morris (SP)

- Detroit Tigers (1977-90), Minnesota Twins (1991), Toronto Blue Jays (1992-93), Cleveland Indians (1994)

- Career: 254-186 (.577), 3.90 ERA, 2,478 strikeouts

- Career: 175 complete games, most of any MLB pitcher since 1975

- 3-time 20-game winner

- 5 times in the top 5 of Cy Young Voting (7 times in the top 10)

- 4-time World Series Champion (with 3 different teams) (did not pitch in 1993)

- Career: 7-4, 3.80 ERA in 13 post-season starts

- 5-time All-Star (started 3 times)

- Opening Day starter for 14 consecutive years (1980-1993)

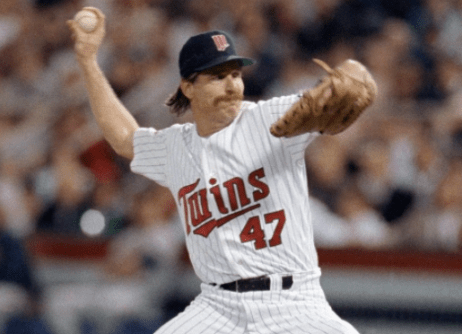

(cover photo: Baseball Hall of Fame)

Jack Morris: Career Highlights

John Scott Morris, born in 1955 in St. Paul, Minnesota, was the Detroit Tigers’ 5th-round draft pick in 1976, the same draft in which they plucked his longtime teammate Alan Trammell. Morris had just completed his junior year at Brigham Young University, in which he was transformed from a wild thrower into a well-rounded pitcher by Vern Law, the long-time Pirate and 1960 Cy Young Award winner whose son Vance was Jack’s teammate at BYU.

Just a little over one year after he was drafted, Morris made his debut with the Tigers in relief. In his second career MLB appearance, he was the Tigers’ starting pitcher, matched up in Arlington, Texas against future Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven. It wasn’t quite like Game 7 1991 but Morris and the Flying Dutchman matched deuces, each throwing 9 innings of 2-run ball before the Rangers prevailed in the bottom of the 10th.

Arm troubles limited Morris to just 138.2 innings in the rest of ’77 and ’78. After starting the 1979 season at AAA Evansville (the hometown of fellow Modern Game ballot member Don Mattingly), Morris was back with the Tigers for good on May 13th. Despite the late start, Morris went 17-7 with a 3.28 ERA in 27 starts and 197.2 innings.

After somewhat of an off-year in 1980 (16-15, 4.18 ERA), Morris emerged as a star in the strike-shortened 1981 season. He was selected to pitch the All-Star Game (which was the first game played after the strike) and finished the campaign at 14-7 with a 3.05 ERA, good enough for a 3rd place finish in the A.L. Cy Young Award voting.

Morris had another less-than-stellar season in 1982 (17-16, 4.06 ERA). According to his SABR bio, he was having problems with his slider and was looking for a “strike three” pitch. It was around that time that Morris discovered the forkball, or split-fingered fastball. Although Tigers pitching coach Roger Craig is often credited with teaching him the pitch, Morris credits his veteran teammate Milt Wilcox, who said he watched future Hall of Fame closer Bruce Sutter throw it when they were both in the Chicago Cubs’ organization. Wilcox couldn’t throw it himself because his fingers were too short but Morris turned it into his “out pitch.”

Morris started throwing the splitter in 1983 and, for five years, was one of the top starters in the American League. For those five years, he led all A.L hurlers in wins, complete games, strikeouts, and BAA (batting average against) and (for pitchers with at least 1,000 innings tossed) was 2nd in ERA. He made three All-Star games during those five seasons and had two top 5 finishes in the Cy Young voting. He won 20 games twice, averaging 19 wins during those five years.

The Great 1984 Detroit Tigers

For the Tigers, of course, 1984 was the glory year. Although, ironically, it was Morris’ worst of those five campaigns, he got the season going like gangbusters. He was manager Sparky Anderson‘s choice to start Opening Day (for the fifth straight year) and tossed 7 innings of one-run ball against his hometown Minnesota Twins. In his second start of the season, he led the Tigers to their fourth straight victory by tossing a no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox.

Detroit famously went 35-5 to start the ’84 season. The ace right-hander’s contribution, in 11 starts, was a 9-1 record with a 1.97 ERA and 6 complete games. Morris went through a mid-summer swoon (a 6.92 ERA in 12 starts between June 12th to August 16th) but finished strong with a 2.85 ERA in his last 9 starts and a 1.42 in his final three. In the post-season, Morris was a true ace, going 3-0 with a 1.80 ERA, which included two complete games in the World Series, which the Tigers won in 5 games over the San Diego Padres.

At the end of Morris’ five-year run of excellence (1987), the Tigers were in a heated battle with the Toronto Blue Jays for the A.L. East title. Needing a boost to their starting rotation, General Manager Bill Lajoie made a trade on August 12th, trading a young pitching prospect to the Atlanta Braves for veteran right-hander Doyle Alexander, who led the Tigers to the playoffs by going 9-0 with a 1.53 ERA in 11 starts. The playoff appearance came at a high price, however. That young pitching prospect was named John Smoltz.

For the only time in his career, Morris was supplanted as his team’s #1 starter. Alexander started (and lost) both Games 1 and 5 of the ALCS to the Twins. Morris, pitching in Game 2 against Blyleven at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, gave up 6 runs in 8 innings and took the loss. The Twins completed a 4-1 series win when Blyleven beat Alexander in Game 5.

If Morris had been able to maintain his form from 1983-87 for the succeeding five seasons, we wouldn’t be still arguing about whether he was a Hall of Famer or not. From 1988-90, he went 36-45 with a 4.40 ERA. During this down period, in ’89, he had elbow surgery for a stress fracture. Even in these three down years, Morris remained a workhorse; his 31 complete games during these years were second only to Oakland’s Dave Stewart.

Home in Minnesota

Things turned around in 1991 when Morris signed a one-year contract with his hometown Twins. He went 18-12 with a 3.43 ERA, leading the Twins back to the playoffs. After winning Games 1 and 4 of the ALCS (against the Toronto Blue Jays), he opened the World Series at the Metrodome against the N.L. champion Atlanta Braves. Tossing 7 innings of 2-run ball, he won that game. In Game 4, pitching at Fulton-County Stadium in Atlanta on three days rest, he gave up just one run in 6 innings but was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the top of the 7th and had a no-decision.

Of course, again pitching on three days rest, he delivered the World Series to Minnesota with his 10-inning shutout in Game 7, besting Smoltz, that young pitcher the Tigers had traded to get Alexander just four years before. Big Game Jack’s Game 7 performance was the vintage start for an ace. He talked manager Tom Kelly out of replacing him in the 10th inning and delivered a perfect frame on 8 pitches; he was the winning pitcher when Gene Larkin delivered a bases-loaded single in the bottom of the 10th.

From his SABR Bio:

“I probably had the best mindset in that game that I’ve had in any game in my whole career, and that’s because I didn’t allow negative thoughts into my game… If I could bottle that, I’d be the richest man in the world. If I could bottle it and sell it to athletes or sell it to businessmen or whatever, it would be a phenomenal thing. I can hardly even describe it, but I can tell you it was something I had never experienced before and really never experienced again.”

— Jack Morris (in his Bio by the Society of American Baseball Research, by Stew Thornley)

Final Years in Toronto and Cleveland

After the title run, Morris disappointed Twins fans by taking a bigger money offer to sign with their ALCS opponents, the Blue Jays. He led the Jays in wins with 21 (against 6 losses), leading the talented squad back into the playoffs. Toronto won their first of two consecutive World Series titles but this time, without a significant contribution from their #1 starter. Morris went 0-3 with a 7.43 ERA in four post-season starts.

As many players do, the long-time workhorse finished his career on a down note. He went 7-12 with a 6.19 ERA with the ’93 Jays and 10-6 with a 5.60 ERA with the Cleveland Indians in 1994.

Morris had a chance to make a comeback with the New York Yankees in 1996 but turned down the offer because they wanted him to make two starts in the minor leagues first, a decision he would later regret because he could have added to his collection of three World Series rings. And thus his career was over at the age of 41.

All in all, Morris finished with 254 wins, a 3.90 ERA, and 175 complete games, which remains the most in baseball for any pitcher since 1974.

The Hall of Fame Case Against Jack Morris

The case against Jack Morris as a Hall of Famer is fairly compelling and you don’t need modern sabermetrics to make it. All you have to do is look at his career Earned Run Average of 3.90, which is the highest for any pitcher with a Cooperstown plaque. ERA can be understood by third-grade mathematics. Using Earned Runs allowed (ER) and Innings Pitched (IP), the formula is simple. ER*9/IP. Simply put, an ERA of 3.90 means that Morris allowed nearly four earned runs per 9 innings and that’s a higher number than anyone currently in the Hall.

Moving on to advanced metrics, when accounting for ballpark effects and the overall pitching environment during his 18 years on the mound, his ERA+ is just 105. If you’re not familiar with it, ERA+, as shown on Baseball Reference, sets 100 as league average every season. Of the 68 pitchers currently enshrined in the Hall of Fame, only Catfish Hunter (104) and Rube Marquard (103) have a career ERA+ lower than the 105 authored by Morris.

The second plank in the case against is that his career WAR (43.6) is low. Only 13 Hall of Fame pitchers have a lower WAR; five of them are relief pitchers. All told, Morris’ WAR, according to Baseball Reference, is just 143rd best for pitchers in baseball history. He’s behind luminaries such as Brad Radke, Bartolo Colon, Kenny Rogers, and his teammate Frank Tanana on this list.

(If you’re a new reader and don’t know what WAR is, it stands for “Wins Above Replacement.” The goal of this statistic is to show, in a single number, how valuable each player was in terms of how many games he helped his teams win as opposed to a replacement player, defined as someone you could find at the top level of the minor leagues. The breakdown of how WAR is calculated for pitchers can be found here in the Glossary.)

The third plank in the case against is that Morris’ 254 wins, a solid total, is inflated because of the quality of the teams he played for. Throughout his career, his teams scored 4.9 runs per game in his starts. That’s half a run higher than the average run support for all MLB pitchers during the 18 years that he played. In his book The Cooperstown Casebook, Jaffe asserts that Morris’ career win-loss record, equalized by the Pythagorean Theorem, would be 234-206 instead of the 254-186 that it actually is.

The fourth plank in the case against Morris is that his record is also inflated by the superior defensive squads that he pitched for. Take a look at the Tigers’ WAR leaders during Morris’ best five seasons (1983-1987).

| 1983-1987 Tigers | Position | WAR |

|---|---|---|

| Alan Trammell | SS | 30.3 |

| Lou Whitaker | 2B | 23.6 |

| Chet Lemon | CF | 23.1 |

| Jack Morris | SP | 21.6 |

| Kirk Gibson | RF | 20.1 |

The argument is that Morris was the beneficiary of the defensive skills of Trammell, Lou Whitaker, and Chet Lemon. All three have a career WAR significantly higher than Morris’, with a significant portion of their value being attributed to defensive metrics. Also, Morris’ career BABIP (batting average on balls in play) was .272, a full 14 points lower than the MLB average during his 18 years on the hill. The argument is that BABIP is inherently a function of the quality of a pitcher’s defense.

Trammell, of course, went into the Hall with Morris in the summer of 2018. His career WAR is 70.7 compared to Morris’ 43.6. Whitaker’s is even higher (75.1). Lemon’s mark is 55.6.

“To go into the Hall of Fame with my friend and teammate Alan Trammell is a dream come true. We signed together in 1976, spent 13 years together in Detroit, and now 42 years later, Cooperstown. Wow, wow.”

— Jack Morris (Hall of Fame induction speech, July 29, 2018)

The fifth plank in the case against is that Morris was not the legendary post-season pitcher that we think of because of Game 7 in 1991. His overall October mark is 7-4 with a 3.80 ERA, which is a reflection of his regular season record. He pitched some great games to be sure but tossed several clunkers as well, especially in 1992 with the Blue Jays.

Ouch. This is all a pretty compelling case against.

“I didn’t grow up learning the analytics that are in the game today. None of it was part of it. I always found it puzzling to wonder why I’m being judged on a criteria that didn’t even exist when we played.”

— Jack Morris (on espn.com, December 10, 2017)

The Hall of Fame Case For Jack Morris

The case that Jack Morris is a worthy Hall of Famer rests upon five arguments:

- He was a big game pitcher who helped his teams win championships, epitomized by Game 7 in 1991.

- He was an innings eater who saved his bullpens by pitching deep into ballgames.

- Why the wins matter.

- He was the most important pitcher of his generation.

- WAR, being an approximation subject to multiple subjective choices by its inventors, does not adequately reward Morris for his performance. Yes, folks, I’m going to go to war with WAR.

The “He Helped His Teams Win” Argument

Let’s start with the “big game” reputation. As we saw at the end of the “case against,” Morris’ post-season record contains some great performances but also some poor ones.

In 1992, whether it’s by WAR or by ERA, Morris (who went 21-6 with a 4.04 ERA) was actually Toronto’s fourth-best starting pitcher, behind Juan Guzman (16-5, 2.64 ERA), Jimmy Key (13-13, 3.53 ERA) and mid-season acquisition David Cone (4-3, 2.55 ERA in 8 appearances).

When he was on the hill, Morris was rewarded with 5.6 runs per start by his team’s hitters, a full run per start better than Guzman received so let’s accept for the moment that maybe the 25-year-old Guzman deserved to be the team’s 20-game winner. Still, in 12 of Morris’ wins, he pitched at least 7 innings and gave up 2 runs or less. In two other wins, he pitched into (but didn’t finish) the 7th and gave up 2 runs or less. In another win, he tossed 8 innings of 3-run ball. In another, he did the minimum for a quality start, 6 innings of 3-run ball. In fairness, he had 5 cheap wins in which he gave up 4 or more earned runs.

In the Blue Jays’ 1992 World Championship run, Morris went 0-3 with a 7.43 ERA so it’s fair to say his team gave him that third ring, just as Morris was almost single-handedly responsible for the Twins’ 1991 title. So, it’s true that Big Game Jack’s overall post-season ERA (3.80) is nothing special but it’s because of that one post-season. In his first 9 October starts, Morris went 7-1 with a 2.60 ERA.

What’s the point of this boring story? The point is that, in the regular season, Morris won 21 games and the Blue Jays won the division by just four games. Even if we discount his five cheap W’s, it’s fair to say that the Jays would not have made the 1992 post-season without the free-agent acquisition of Jack Morris.

If you wanted to invent a category called “Rings Above Replacement” (how many rings did a player help his team win), Morris probably deserves two. The ’91 Twins absolutely positively won the Fall Classic because of Morris. The ’92 Jays might not have made the playoffs without Jack on the hill for his 21 wins. The ’84 Tigers were a superteam (they won the A.L. East by 15 games) so the loss of any one player wouldn’t have kept them out of the playoffs. However, it’s unknown if the team would have won the World Series without Morris’ two complete games (won by scores of 3-2 and 4-2). So, let’s give him one “Ring Above Replacement” for his essential role in ’91 and half a “Ring Above Replacement” for his post-season contribution in ’84 and his regular season contribution if ’92.

A lot of Hall of Fame voters look upon post-season heroics as “extra credit” for a Cooperstown resume. I put much, much more stock into October baseball. For me, his 1991 Game 7 ten-inning shutout was worth 30 to 50 regular season wins.

He didn’t always deliver in October but he did it twice and in a big way.

The Innings Eater

Whether you think he deserved his Hall of Fame election or not, there’s no doubt whatsoever that Morris was a workhorse. 7 times in his 18 seasons, Morris was in the top five in the American League in Innings Pitched. In 7 different seasons, he was in the top three in the A.L. in Complete Games. Starting in Morris’ rookie season, here is the list of the top 5 pitchers in baseball with the most Complete Games, with the percentage of their games started that they completed.

| Pitcher | CG | GS | % CG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jack Morris | 175 | 527 | 33.2% |

| Bert Blyleven | 127 | 436 | 29.1% |

| Dennis Martinez | 121 | 560 | 21.6% |

| Roger Clemens | 118 | 707 | 16.7% |

| Fernando Valenzuela | 113 | 424 | 26.7% |

What makes Morris’ total all the more remarkable for his generation was that, for 11 1/2 of his 18 seasons, his manager was Sparky Anderson, who was known as Captain Hook when he was skippering the Cincinnati Reds dynasty in the 1970s. Nobody went to the bullpen more often than Sparky but, in the A.L. and the lack of need for pinch-hitting for the pitcher, in Morris he found a horse that he trusted to go the distance. Morris completed nearly a third of his starts in his entire career. In his years with Anderson at the helm in the dugout, he completed 151 out of 387 starts (39%).

But it wasn’t just the complete games. Morris went deep into games (8+ innings) more than any pitcher in the last 43 years.

| 1977-2019 | 8+ IP | GS | % 8+ IP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jack Morris | 248 | 527 | 47% |

| Roger Clemens | 232 | 707 | 33% |

| Greg Maddux | 214 | 740 | 29% |

| Randy Johnson | 192 | 603 | 32% |

| Dennis Martinez | 190 | 560 | 34% |

If you take out the first two and the last two years of his career and look just at the 14 years when he was a full-time starter (and qualified for the ERA title), he went 8 or more innings in 241 out of 464 starts (52%). The second-highest total for those 14 years belongs to Charlie Hough (who made 166 starts of 8+ IP).

Interestingly, the 8th inning was Morris’ worst. In his career, his 8th-inning ERA (4.47) was the worst of all 9 innings of the game. When Morris reached the 9th, however, he was highly effective, posting a 2.78 ERA in 165.1 innings while holding opposing batters to a .208 average.

“In 1980, I was struggling late in games. Sparky (Anderson) told me he had confidence in me, but that I needed to finish games to rest the bullpen. He said he couldn’t tell me how to do it, wasn’t coming out to get me, so I shouldn’t look for any help. He taught me a valuable lesson by allowing me to fail and fight through adversity.”

— Jack Morris (Hall of Fame induction speech, July 29, 2018)

Morris as 9th inning closer:

Don’t worry. There wasn’t a Smoltz-esque part to the career of Jack Morris that you missed. Morris only appeared out of the bullpen 22 times in his career, all but one of those appearances in 1978. What I was curious about was how he performed in the 9th inning in what would have been a save situation if a new pitcher had entered the game.

To do this, I went through all of Morris’ career game logs on Baseball Reference, downloaded and sorted them, focusing on the games in which he pitched into the 9th inning. There were 68 games in his career where Morris went out to finish the game in what would have been a save situation for a closer (a lead of 1 to 3 runs).

In those games, Morris (had he been a closer as a clone of himself) would have been credited with a save 49 times, with just 3 blown saves. In 10 other games, he would have gotten what today we call a “hold,” where he held the lead but didn’t finish the game. In 5 games, he allowed the first batter to reach base and was taken out after that one batter.

All told, his performance as the “closer” to his own games is pretty darn great for someone who had already labored for 8 innings: 49 saves, 10 holds, 3 blown saves, and a 2.97 ERA.

Since the mound was lowered in 1969, there have been 16 pitchers who started at least 150 games in which they pitched into the 9th inning. Those 16 include 10 Hall of Fame starters from the 1970s plus Morris, Tommy John, Tanana, Vida Blue, Jerry Koosman, and Jerry Reuss.

Here are the five best in both ERA and batting average against (BAA).

Best ERA and BAA for pitchers in the 9th inning (1969-2019):

| Top 5 | ERA | Top 5 | BAA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steve Carlton | 2.74 | Nolan Ryan | .204 | |

| Jack Morris | 2.78 | Jack Morris | .208 | |

| Tom Seaver | 2.85 | Phil Niekro | .223 | |

| Gaylord Perry | 2.89 | Vida Blue | .228 | |

| Phil Niekro | 3.00 | Steve Carlton | .240 |

Morris’ 9th inning record and ERA are this low despite the fact that, during the games in which he was relieved during the 9th inning, he is credited with 51 earned runs allowed but 40 actual runs allowed. This means that 11 earned runs were charged against him because those succeeding him on the mound allowed the inherited runners to score. This is the highest number among the 16 starting pitchers who have 150 or more games pitched in the 9th.

Don’t Kill the Wins

In the sabermetric community, there is a movement, led by MLB Network’s Brian Kenny, to “kill the win.” The concept is that wins and losses are subject to the randomness of run support and bullpens blowing leads to cost a starter his win or a team rallying to take a starter off the hook for a loss. In today’s game, where more relief pitchers are used than ever before, killing the win might make sense. But when Jack Morris was pitching, wins still mattered.

In the short version of the Morris Hall of Fame case, it’s that he won the most games in the 1980s. He had 162 wins in the decade, 22 more than runner-up Dave Stieb.

“Most wins in the ’80s” is a junk stat, like “OPS from Aug. 24 through [the] end of season” or “batting average in day games in even-numbered innings during Ramadan.” You know, the kind of thing stupid people think is sabermetrics.

— Jason Brannon (SB Nation, Dec. 17, 2012)

Brannon has a point and I partially agree with it. However, his comparative example of OPS from Aug. 24 through the end of the season is meant to amuse; a period of ten years represents a large sample size and is not to be completely discounted.

It’s true that, by choosing a particular decade, you are in essence gerrymandering the results for a player or pitcher who happened to toil during the years in question. But, on Baseball Reference, we can also look at who led the majors in wins from 1978-1987 or from 1983-1992, or any other period in time you wish to analyze.

The truth is that Jack Morris led all of MLB in wins in the 10-year periods from 1977-86, from 1978-87, 1979-88, 1980-89, 1981-90, 1982-91, and 1983-92. For seven consecutive rolling periods of 10 years, Morris won more games than anybody else in baseball. If you do this once, maybe it’s a fluke, but seven times?

Look at the names of the other pitchers with at least six 10-year periods in time in which they had the most wins.

| Pitcher | # of times led MLB in Wins for 10 years | 10-year periods with most wins in MLB |

|---|---|---|

| Greg Maddux | 12 | 1987-96 thru 1996-05 and 1998-07, 1999-08 |

| Warren Spahn | 11 | 1945-54, 1946-55, and 1948-57 thru 1956-65 |

| Lefty Grove | 8 | 1923-32 thru 1930-39 |

| Jack Morris | 7 | 1977-86 thru 1983-1992 |

| Walter Johnson | 7 | 1907-16 thru 1913-22 |

| Christy Mathewson | 7 | 1900-09 thru 1906-15 |

| Cy Young | 7 | 1882-01 thru 1898-07 |

| Steve Carlton | 6 | 1971-80 thru 1976-85 |

| Hal Newhouser | 6 | 1939-48 thru 1944-53 |

That’s some pretty strong company, don’t you think? In fact, if you take the list of every pitcher to lead the majors in wins for a 10-year stretch, going from 1878-87 to 1999-08, all but two pitchers are in the Hall of Fame.

The non-Hall of Famers are Paul Derringer, who led all MLB in wins from 1934-43, and Bucky Walters, who has the honor for four cycles in a row, 1935-44 through 1938-47. Derringer legitimately had the most during his years, besting Red Ruffing by 3 wins. Walters, however, likely owes the honor because the best pitcher in baseball at the time, Hall of Famer Bob Feller, lost nearly four years from 1942-45 serving in World War II. Rapid Robert led either the majors or the A.L. in wins in the three years prior and two years after his military service.

The key element of this discussion is to clearly understand that, in the case of Morris, his wins mattered. He also led all of MLB in complete games for 9 consecutive 10-year cycles (from 1977-86 through 1985-94). By being the workhorse who finished more games than any other pitcher in his generation, he won more games than any other pitcher in his generation. That matters.

Morris also led the majors in innings pitched from 1978-87 and the next five 10-year cycles after that. The workload for this workhorse eventually caught up to him. After averaging 241 innings pitched for 13 seasons, he fell to 152.2 in 1993 and 141.1 in ’94, with his productivity shot. Because he wasn’t able to pitch into his 40’s, Morris fell short of the traditional Hall of Fame benchmark of 300 wins. Take a look, though, at how he ranks among all MLB pitchers who logged less than 4,000 career innings.

| Pitcher | IP | W | L | WL% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Lefty Grove | 3940.2 | 300 | 141 | .680 |

| *Mike Mussina | 3562.2 | 270 | 153 | .638 |

| *Jim Palmer | 3948.0 | 268 | 152 | .638 |

| *Bob Feller | 3827.0 | 266 | 162 | .621 |

| Andy Pettitte | 3316.0 | 256 | 153 | .626 |

| *Jack Morris | 3824.0 | 254 | 186 | .577 |

| *Carl Hubbell | 3590.1 | 253 | 154 | .622 |

| *Bob Gibson | 3884.1 | 251 | 174 | .591 |

| CC Sabathia | 3577.1 | 251 | 161 | .609 |

| *Hall of Famer |

At the time his career ended (after 1994), Morris had 254 wins. At that time, only two pitchers (Tommy John and Jim Kaat) had more wins among pitchers who would not eventually get into the Hall of Fame.

The win total for Morris matters. They mattered then. They matter now.

Best (or Most Significant) Pitcher of his Generation?

From 1962 to 1970, ten different starting pitchers who would eventually make the Hall of Fame made their MLB debuts: Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Catfish Hunter, Jim Palmer, Fergie Jenkins, Steve Carlton, Don Sutton, Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver, and Bert Blyleven. All ten made their marks primarily in the 1970s. The only one of the ten to whom Morris compares favorably (at least statistically) is Catfish (224-166, 3.26 ERA, 104 ERA+).

From 1986 to 1992, six different starting pitchers who would eventually make it into the Hall made their debuts: Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, John Smoltz, Randy Johnson, Mike Mussina, and Pedro Martinez. Maddux, Martinez, and Johnson are all-time greats.

Until Jack Morris’ enshrinement in 2018, there was not one Hall of Fame starting pitcher who made their major league debut during the years 1971 to 1985 (a 15-year span). Even if you take note that Roger Clemens, who would normally have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer, debuted in 1984, there had still been a 13-year period that did not feature the debut of a single Cooperstown inductee as primarily a starting pitcher. Since Morris debuted in 1977 (right in the middle of that span), it’s fair to say that he is the first and only pitcher from his generation to make it into the Hall of Fame.

From 1971 to 1983, there were 54 different pitchers who premiered in the big leagues and would go on to have careers in which they logged at least 2,000 innings. Only one other of those 54 hurlers (Dennis Eckersley) is in the Hall of Fame and he’s there because of his dual career as starter and closer.

In the previous 13 years (1958-1970), 62 pitchers debuted who would go on pitch at least 2,000 MLB innings; 12 of those 62 have plaques in Cooperstown.

If you have triskaidekaphobia, I apologize for using 13-year windows on this chart.

| Years | Pitcher Debuts | Pitchers in the HOF |

|---|---|---|

| 1871-1879 | 11 | 2 |

| 1880-1892 | 40 | 7 |

| 1893-1905 | 40 | 10 |

| 1906-1918 | 49 | 11 |

| 1919-1931 | 37 | 5 |

| 1932-1944 | 30 | 5 |

| 1945-1957 | 32 | 6 |

| 1958-1970 | 62 | 12 |

| 1971-1983 | 54 | 2 |

| 1984-1996 | 49 | 6 |

The 13-year windows of time are somewhat random, designed to fit the 1971-1983 gap. I could have chosen 15 years, since Clemens (debuting in ’84) is actually not in the Hall of Fame due to his use of PEDs. The first window (1871-1879) is only 9 years long because recorded baseball history starts in 1871.

The point here is that, during the period of time spanning 1971 to 1983, the only four Hall of Fame pitchers other than Morris who debuted were primarily or exclusively relievers (Eckersley, Goose Gossage, Bruce Sutter and Lee Smith).

Morris vs. Stieb

In the analytics community, there is a wide consensus that Dave Stieb, not Jack Morris, should be the Hall of Fame representative from their generation of starting pitchers. Whenever Morris advocates throw out the “most wins in the 1980’s” argument, Dave Stieb advocates throw back the Toronto right-hander’s significantly superior run-prevention metrics.

Let’s start by saying that it is an absolute fact Stieb has better run-prevention numbers during the totality of the two hurlers’ careers. He gave up fewer hits, home runs, and walks per 9 innings than Morris did in his career.

From 1980-85 (a six-year span), Stieb was the best pitcher in baseball. He had the highest WAR (by a lot), the best ERA+ (by a lot) in all of baseball and the lowest ERA, WHIP, and BAA in the American League.

If you take a look at where the two hurlers stood after the 1990 season (an All-Star campaign for Stieb and a poor one for Morris), the only advantage to Morris is the win total (due to completing more starts and pitching on better teams in the early 1980s).

Morris vs. Stieb (1977-1990)

| Pitcher | GS | IP | W | L | WL% | CG | HR | ERA | ERA+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris | 408 | 3042.2 | 198 | 150 | .569 | 154 | 321 | 3.73 | 108 | 37.7 |

| Stieb | 382 | 2666.2 | 166 | 123 | .574 | 101 | 205 | 3.34 | 126 | 55.4 |

If both players’ careers ended after 1990, I would have to rank Stieb above Morris. Other than the wins, his numbers were better. Also, he made 7 All-Star teams in the 1980s (which included 2 starts) compared to 4 for Morris.

But their careers didn’t end after 1990. Morris signed a free-agent contract with Minnesota for 1991 (and won the World Series) and then signed with Stieb’s Blue Jays in 1992 (and won the World Series). In the meantime, Stieb was hurt for most of both seasons and didn’t appear in either post-season.

| Pitcher | Year | Team | IP | W | L | ERA | ERA+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris | 1991 | MIN | 246.2 | 18 | 12 | 3.43 | 125 | 4.3 |

| Stieb | 1991 | TOR | 59.2 | 4 | 3 | 3.17 | 134 | 1.6 |

| Morris | 1992 | TOR | 240.2 | 21 | 6 | 4.04 | 101 | 2.8 |

| Stieb | 1992 | TOR | 96.1 | 4 | 6 | 5.04 | 81 | -0.2 |

After 1992, Morris had two mediocre campaigns (17-18, 5.91 ERA combined) in ’93 with Toronto and ’94 with Cleveland. Stieb pitched just 22.1 innings in 1993 with the Chicago White Sox, missed the next four seasons, and, in a ’98 comeback with Toronto, posted a 4.83 ERA in 50.1 innings.

All in all, although Stieb’s career ERA of 3.44 and WAR of 56.5 were far superior to Morris’ 3.90 ERA and 43.6 WAR, Morris finished with 78 more wins. All team sports are ultimately about wins, losses, and championships. Morris won more games. Morris helped his teams win the World Series three times; Stieb didn’t.

It’s true that Morris had more chances to win rings (four playoff appearances to Stieb’s two) but Stieb did not acquit himself well in the biggest moments of his two bites at the post-season apple. In 1985, the Blue Jays had a 3-to-1 series lead over the Kansas City Royals, thanks in part to two starts from Stieb in which he gave up just one run in 14.2 innings. But the Royals won Game 5 at home and Game 6 in Toronto, setting up a Game 7 showdown at Exhibition Stadium. The Jays’ ace right-hander gave up 6 runs in 5.2 innings and the Royals went on to win the World Series.

Then, in 1989, the Jays, again A.L. East champions, matched up with the Oakland Athletics. Stieb was the starter and loser in both Game 1 and the decisive Game 5, posting a 6.35 ERA in those two starts. It’s a small sample size to be sure but Stieb had two October “win or go home” starts and lost them both. Morris had one and pitched 10 innings of shutout ball.

Stieb, by the way, has a pragmatic view of his own Cooperstown worthiness, In a recent interview with The Sporting News, he acknowledged that he “didn’t belong” in the Hall of Fame because he “didn’t win enough games.” He wasn’t happy, however, about being drummed off the BBWAA ballot after one year; he got just 7 votes (1.4%) on the 2004 ballot, saying “please amuse me and string me out for two or three years.”

Stieb, who today is very aware of his superior WAR, did say that “ERA is indicative of who’s better” but was highly complimentary of his 1992 teammate in Toronto:

“He was an awesome pitcher. He was an animal, a bulldog-like [workhorse], and wanted to win like no one else. I totally respect him and his skills and what he did. But if you had to look at everything, I think I was the best.”

— Dave Stieb (about Jack Morris and himself) (in The Sporting News, Feb. 21, 2017)

Pound for pound, Stieb is right. He was the better pitcher. But showing up counts too. Morris started 115 more games, pitched 928.1 more innings, and won 78 more games.

If you’re picking a “pitcher for the ’80s,” just the 1980s and not beyond, I’d be inclined to agree with the selection of Dave Stieb. If you’re picking the most historically important pitcher of his generation, it’s Jack Morris. If you’re picking a Hall of Famer, it’s Morris.

Last fall, I took a more detailed look at Stieb’s Cooperstown candidacy. Click here for more.

The Sabermetric Argument for Jack Morris

Three of the arguments against Jack Morris for the Hall of Fame are that his career ERA was high, that his WAR was low, and that he had the benefit of great defensive teams behind him (notably the keystone combo of Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker). We’re going to tackle all three of those arguments here.

Morris had a career ERA of 3.90, which is the highest for any pitcher in MLB history in the Hall of Fame. It’s notable though, that Morris spent his entire career pitching in the American League, with the designated hitter, and all but one season in the rugged A.L. East. His career started in 1977, four years after the advent of the DH. It ended after the 1994 season, three years before the debut of interleague play in regular season games.

In his career, Morris faced 16,120 position players and not one pitcher. There is no hurler in the history of baseball with more position players faced without ever having the benefit of the “easy out” that the opposing pitcher usually provides.

Now, it’s true that ERA+ (the park-and-year-adjusted version of ERA) is supposed to take this into account. Therefore, Morris’ 3.90 career ERA is adjusted to a 105 ERA+ for the fact that he was an A.L. pitcher. It can’t, however, account for the cumulative wear and tear of pitching over an average of 245 innings without ever getting that “easy out” break.

If you take the 50 pitchers with the most “non-pitchers” faced since 1973, Morris’ .247 BAA (batting average against) is 11th best. He’s behind 7 Hall of Famers, Stieb, Charlie Hough, and David Cone.

To use an example of the significance of this A.L. only factor, I’m going to pick one pitcher who is behind Morris on this list and offer a side-by-side comparison. That one pitcher is Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, a 305-game winner, who spent his entire career in the N.L.

| vs Non-Pitchers | IP | PA | BAA | OPS | ERA |

| Tom Glavine | 4023.1 | 17276 | .268 | .726 | 3.79 |

| Jack Morris | 3824.0 | 16120 | .247 | .693 | 3.90 |

| vs Opposing Pitchers | IP | PA | BAA | OPS | ERA |

| Tom Glavine | 390.0 | 1328 | .118 | .289 | 0.90 |

| Jack Morris | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

This is not to take anything away from Glavine, a worthy Cooperstown inductee, but he had the enormous benefit of spending nearly two full seasons’ worth facing his opponents’ pitchers. The point here is that, when analyzing what Morris did, the workload that he shouldered in lineups that were stacked 1-to-9 needs to be taken into consideration. Morris’ results against non-pitchers, from a batting average and OPS perspective, are significantly superior to the numbers of a first-ballot Hall of Famer. The lack of easy outs has a collateral impact on a pitcher’s ERA.

The Complexities of WAR

First of all, let me say that I believe in Wins Above Replacement and the goal of its existence. It’s the only statistic that has the ability to measure position players against pitchers. It’s a good way to try to compare players across eras. It’s a useful sorting tool to determine the overall worthiness or lack thereof of a group of players. But WAR must also be looked upon with skepticism. The outcomes of the mathematical formulas are objective but the creation of those formulas requires subjective judgment calls by its creators. Many of you may not know this but there are multiple versions of WAR. The one that we cite most of the time on “Cooperstown Cred” is from Baseball Reference but there are two other mainstream versions, one from Fan Graphs and the other from Baseball Prospectus.

When you start to look at how differently the three websites rate how WAR-thy each player is, you will be stunned at some of the differences and it might make you lose a little faith in the entire process. The way that WAR ranks pitchers on the three sites has the highest level of variation. There is a lot about pitcher performance that is subject to factors beyond each man’s control. The pitcher has no control over the quality of the defense behind him. The pitcher has no control over the dimensions of the ballpark he’s pitching in or the wind direction. The pitcher has no control over the quality of the opposing lineup. He has no control over who is umpiring behind the plate and whether said umpire favors hitters or pitchers.

Finally, to a certain extent, and this is the biggest mystery, the pitcher doesn’t have total control over what happens when the ball is put into play. To make a complex subject as simple as possible, Baseball Reference uses a runs-allowed formula (both earned and unearned) with adjustments for the ballparks and quality of defense behind the pitcher. Fan Graphs’ WAR for pitchers is based on a concept called Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), which relies on the things that a pitcher does in which the defense has no control (issuing walks, getting strikeouts, and giving up home runs).

Baseball Prospectus has a version (called WARP, adding the word “Player” after “Replacement”) which incorporates a unique metric called DRA (Deserved Run Average). DRA micro-targets the batter-by-batter performance of each pitcher, zooming in on the quality of each opposing hitter, the defense, the catcher, the umpire, and the ballpark.

If you’re a believer in WAR and a Morris detractor, this is going to blow your mind. Take a look at the different WAR calculations for Morris and other notable starting pitchers that we’ve been discussing (and some we haven’t) and see how different the results are across the three websites.

These numbers are for pitching only. PWARP is “Pitching WAR” for Baseball Prospectus.

| Pitcher WAR | fWAR | bWAR | PWARP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tommy John | 79.6 | 62.1 | 36.9 |

| Rick Reuschel | 68.5 | 67.1 | 42.3 |

| Tom Glavine | 66.7 | 73.9 | 59.4 |

| Frank Tanana | 58.9 | 57.1 | 48.4 |

| Jim Palmer | 56.8 | 67.6 | 59.7 |

| Jack Morris | 55.8 | 43.6 | 50.4 |

| Dennis Martinez | 49.1 | 49.3 | 55.6 |

| Orel Hershiser | 48.0 | 51.4 | 66.4 |

| Dave Stieb | 43.8 | 56.5 | 23.8 |

Take a moment to linger over some of these numbers for a moment. Depending on which website’s WAR you look at, Tommy John was either great or mediocre. By FanGraphs, Morris was almost as good as Jim Palmer. By Baseball Prospectus, Stieb wasn’t anywhere close to a Hall of Fame quality hurler. It could be the subject of an entire book to explain the whys and wherefores of each pitcher’s wide variance in what each website perceives as their value.

Anyway, there are two ways to respond to this. One is to throw your hands in the air and give up. Obviously, as a writer who analyzes Hall of Fame cases, that’s not the path that I’m going to take.

The reason I showed this, in this piece, is to give some credit to Jack Morris for the things that have been denigrated by the sabermetric community, primarily that he labored his entire career in the unforgiving American League East. Please allow one of the Baseball Prospectus writers to elaborate (from 2015, several years before Morris made it into Cooperstown):

“Our generation of baseball fans and analysts might have been wrong about Jack Morris. Let that sink in for a moment. We yelled and bickered and picked Morris’s career apart, and we won: Morris is not in the Hall of Fame… We told the world, in no uncertain terms, that Morris was an unimpressive compiler, a workhorse without distinctive merit… We might have been right, of course. But it looks a lot like we were wrong… This is a pretty compelling case that we were wrong about Morris, and that we’ve now done irreparable damage to his legacy by seeing that too late… It’s important to remember that no matter what you believe, there will almost surely come a point in the future at which you look stupid.”

— Matthew Trueblood, Baseball Prospectus (June 20, 2015)

Here’s one other really important point about the various WAR calculations as it relates to the subject of our story. One of the narratives in the case against Morris is that a great deal of his success is due to the defensive contributions of Trammell and Whitaker (as well as Chet Lemon in center field). So, let’s look at the three websites and how they rank the relative WAR of Morris and his teammates.

| Career WAR | WARP | fWAR | bWAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alan Trammell | 50.9 | 63.7 | 70.7 |

| Jack Morris | 50.4 | 55.8 | 43.6 |

| Lou Whitaker | 48.5 | 68.1 | 75.1 |

| Chet Lemon | 45.8 | 52.0 | 55.6 |

Nobody who watched the Detroit Tigers in the 1980s would doubt the contributions of Trammell, Whitaker, and Lemon to the success of those teams but the notion that Morris was merely the beneficiary of their excellence defensively deserves a second thought here.

Incidentally, I am also one of the many advocates for Whitaker joining Morris and Trammell in Cooperstown.

The Impact of Tiger Stadium

In his 14 years pitching at Tiger Stadium, Morris had a BABIP (batting average on balls in play) of .265. That’s the fifth lowest in MLB among all MLB pitchers for those 14 years. Since a pitcher’s BABIP is generally considered to be a random act not subject to their own skills, some detractors have actually used that low BABIP as an argument against Morris, making the case that he was merely the beneficiary of a great defense behind him. But take a look at this:

- From 1977-1990, the Detroit Tigers (as a team), had the lowest BABIP of any team in baseball for games played at Tiger Stadium.

- In those same years, the Tigers (as a team) yielded the second most home runs in their home games, second only to the perennial doormat Seattle Mariners.

For road games:

- From 1977-1990, the Tigers (as a team), had a BABIP that was tied for 10th lowest (with three other teams).

- In those same years, the Tigers (as a team), yielded just the 6th most home runs.

Morris, in his 14 years in a Tiger uniform, gave up 25 more home runs at home than he did on the road. His BABIP was 8 points lower at home than it was on the road. These same home/road splits are almost universally consistent with the results of other Tiger pitchers during these 14 seasons. The home run splits are also consistent with longtime Tigers hurlers Jim Bunning, Mickey Lolich, and Denny McLain in past years.

What’s the conclusion? The conclusion is that Tiger Stadium, at least from 1977-90, was a WAR-depressing ballpark for pitchers. The short porch in right field, especially with the upper deck that extended over the field, was highly conducive to home runs. If you have a ballpark that has a high propensity for the long-ball but also a propensity for a low BABIP, that’s going to be to the detriment of the pitchers because home run rates are considered the sole responsibility of pitchers while BABIP is attributed to the excellence (or lack thereof) of the defensive squads behind them.

Closing Thoughts

Whether you’re an advocate or a detractor, there’s no doubt that Jack Morris played an important role in the history of Major League Baseball. From his 14 Opening Day starts, his 3 All-Star Starts. his 3 World Championships and MLB-best Complete Games for the last 41 years, Morris was the personification of a workhorse, an ace.

You can go online and find many sabermetric arguments against Jack Morris as a Hall of Famer. The most thorough is from Sports Illustrated‘s Jaffe, on si.com, which covers some of the material in Chapter 6 of his excellent book, The Cooperstown Casebook. Incidentally, although I disagree with his conclusion here, this is the best book written about the Hall of Fame (in my opinion) since Bill James’ Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame. I will give Jaffe credit for being magnanimous in one of his concluding paragraphs in his beat-down of Morris.

“There’s no real joy in turning away Morris. Many of us who devoted time and energy to arguing against his case grew up watching his no-hitter, Game 7 shutout and other highlights from his 18-year career. We know he was a very good pitcher for a long time, an intense competitor and a sturdy workhorse. It takes a hard heart to avoid acknowledging the man’s pain in being close enough to taste his inevitable election, yet falling short due to forces unforeseen at the outset of his candidacy. He didn’t ask to become a battlefront in a cultural war.”

— Jay Jaffe, “The Cooperstown Casebook” (2017)

I’m not asserting that the analysis of Jaffe and the other critics is necessarily wrong. Based on the numbers as they exist on Baseball Reference, the analysis is valid. And, remember, you don’t need WAR to make that case. Morris’ 3.90 career ERA is the highest of any starting pitcher in the Hall. My argument is that Morris pitched at a unique period in baseball history and, despite many blowout losses that padded his ERA, he was a dominant force during his period in history. My second argument is that his win and complete game totals mattered; they were unique to his particular generation. And my third argument is that the sabermetric science that puts Morris in the below-Cooperstown tier is not settled, as we saw in the last section.

The last line, that the sabermetric science is “not settled,” might one lead one to conclude that we should have waited until it was settled before inducting Jack Morris to the Hall of Fame. My answer to that is that the guy had to wait long enough. Until we invent a time machine and can send a brigade of sabermetricians back in time to document every game in MLB history the way we do it today, we’re never going to exactly know how to properly analyze the statistics for players of Morris’ generation.

His wins are real. His complete games are real. His rings are real. Game 7 was real and if you asked Morris if he would trade that game for 50 more regular season wins, I guarantee you his answer would be an emphatic “No.” As I noted earlier, to me, that 10-inning masterpiece was worth 30-to-50 regular-season wins.

With the exception of the fact that his ERA is the highest (someone has to have the highest), the induction of Morris did absolutely not lower the standards for a Hall of Fame starting pitcher. If you’re going to make a case for a future starter with a 3.90 ERA, they’d better have some other compelling arguments. You would need “Cooperstown Cred” such as having over 250 wins, completing nearly a third of your starts, starting on Opening Day 14 times, and it would help if you would go out and deliver one of the greatest clutch pitching performances in the history of the sport.

The existing group of living Hall of Famers are highly protective of who they admit into their exclusive club. At least six out of eight of those Hall of Famers on the Modern Baseball Committee, all of whom competed against Morris, decided that he was worthy of joining their club, 3.90 ERA and all. Yes, I’m pretty sure that his ERA came up when the 16-member committee deliberated. 14 out of those 16 (thus at least 6 out 8 Hall of Famers) said “yes” to the best big-game pitcher of his generation.

On MLB Network’s MLB Now, the official MLB historian John Thorn made a comment to host Brian Kenny that “Jack Morris should be in the Hall of Fame because he was famous.” That’s not enough, obviously. Morris’ Tigers teammate Kirk Gibson was famous and nobody thinks he should be in the Hall.

The point is that Morris was famous as the game’s durable workhorse long before his epic performance in Game 7 of the ’91 Series. I met Thorn at a SABR conference a couple of months after that MLB Network appearance and we talked about Morris. He made a comment, almost as if he had plucked it directly out of my brain: “It’s the Hall of Fame, not the Hall of WAR.”

So let’s finish by returning to October 27, 1991. It was a matchup between a grizzled War Horse (the 36-year-old Morris) against a Young Gun (the 24-year-old John Smoltz). Baseball is a sport full of great stories. From Jack’s 2018 enshrinement until the end of time, we can now tell that the Game 7 story as a battle of two future Hall of Famers in a winner-take-all contest. The two future Hall of Famers matched zeroes until the War Horse outlasted the Young Gun and almost single-handedly won one of the greatest deciding title games in the history of the sport. The Young Gun was a first-ballot inductee into Cooperstown (in 2015) and now, with the War Horse getting his plaque in 2018, the story is complete.

Thanks for reading.

Chris Bodig

Yes I agree totally that these two make it however, the panel of “experts” are seriously missing the boat thinking they’re doing the hall a service by limiting the new HOF’ers. If a player or exec are deserving they are deserving. Period.

Morris lowers the bar for starting pitchers. Dave Stieb, Ron Guidry, Steve Rogers, Frank Viola, on and on you can name pitchers who you can twist this way and that who were as good as Morris. Heck, Baltimore fans could pick 2 pitchers not named Mussina and have a fine argument now. MLB Hall isn’t as weak as the NBA (Ralph Sampson, Chris Mullin, Jojo White, Mitch Richmond, Tracy McGrady just for starters, sheesh).

I love Jack Morris as much as anyone, however he is not a Hall of Famer. He was elected on his popularity and off the field nice guy persona (sorry Jack) His average WARb for seasons (15) where he started the minimum (162inn) was 3.0. Among his contemporaries, only Tommy John (2.9) was lower over 20 seasons. So Jack sets the new low bar. Until now it was the other misguided selection of one Jim Hunter to the Hall at 3.1 Post season heroics alone don’t make a hall of famer. They can enhance an already valuable contribution made during their regular season career, alas Jack had neither a great peak like Stieb or a great career value like Kevin. Speaking of Kevin Brown, he didn’t have such a great personality or working relationship with the writers and paid dearly for it. With the election of Morris,…what next for the Modern Day committee?

Bare minimum is that Stieb, Cone and Saberhagen have to go in. Jack will become the new low bar relieving Catfish of that lowly distinction.

Perhaps the worst HOF pick ever. 105 ERA+…….OMG. He is not in my HOF. Their are 300-400 pitchers better.

Fantastic article thoroughly researched with “spot on” analysis. Jack Morris is a “no brainer” Hall of Famer in my book. If Jack Morris had pitched for the Yankees or Mets, then Morris would have been a 1st ballot Hall of Famer. The small market Detroit that Morris pitched in has held back Morris, Trammell, Whitaker and other Tigers from serious Hall of Fame Consideration by the Writers. The New York Media appears to have an outsized influence as to who makes the Hall of Fame in the Writers balloting. Remember, in Morris’s Trammell’s and Whitaker’s Era, we did not have the massive TV contracts, sports cable networks with wall to wall baseball games and coverage and multiple MLB games televised every night. East Coast Writers voting on Morris, Trammell and Whitaker were often sleeping when the Tigers games were played in the Central and Western time zones…..Game feeds were not as prevalent etc.. Many East Coast Writers/Voters rarely saw Morris, Whitaker and Trammel play outside the All Star games, the playoffs and the World Series.

Jack Morris was Long Overdue for the Hall of Fame. If Morris played for the Yankees or Mets, then Morris would have been a 1st ballot Hall of Famer…Ditto with Alan Trammel and Lou Whitaker. Detroit Tigers players in recent decades have been given the “short shrift…. Jeter is the 1st Yankee in the Hall of Fame who had 3.000 hits?! In smaller media markets, the Hall of Fame Standards have been either 3,000 hits or 500 home runs or 300 wins or at least 3,000 strikeouts….Hall of Fame standards appear to have been lower for the Yankees and Mets since NYC is MLB Headquarters and the center of the Baseball Writing Media/Hall of Fame Voters etc…Many Yankees players were inducted into the Hall of Fame as a result of playing on great teams.. And although their team accomplishments were great, some of their individual accomplishments were borderline or below Hall of Fame worthy if they had played in Seattle or Detroit, or Milwaukee or Cleveland smaller media markets.

Because of limited televised games at the time, many Writers rarely saw Morris, Trammel Whitaker and other great players toiling in smaller media markets…Yet, Writers “flying blind” still voted on Hall of Fame Candidates?!

Hall of Fame Voting and Consideration needs to be revamped at the 1st stage.

The Veterans Committee is an Important and necessary development in the MLB Hall of Fame selection process. Let’s hope that

Thanks for the article. I have always thought Morris was a HOF’amer. Despite the negatives. I love modern stats, so I hate when I would say about Morris, “I know about the negatives, but he was better than his stats and he just feels like a HOF’mer to me.” I really didn’t have a good (enough argument) to defend my opinion. Your article puts into words some of the things I instinctively felt about Morris’ career. By the way, not long after Morris’ first year on the ballot, I played golf at a Long Island country club and my caddie was a retired Newsday baseball writer, who still had his BBWAA voting rights. I can’t remember his name, but I asked him about candidates on the ballot. He was in the “Morris doesn’t belong camp,” I was unable to persuade him that Morris belongs. I’m glad he is in.

I like how you expanded “most wins the 1980s” to encompass all 10-year spans: but Ron Guidry and Frank Viola need to be added to your “non-HOFer” list. Guidry had 163 wins to lead during 1977-1986, and Viola is tied with Clemens with 163 from 1984-1993. And then Pettitte leads for 2000-2009 with 148, so the 10-year interval isn’t that meaningful. If you want some interesting results regarding Hall-of-Famers, look at 5-year spans: very eye-opening! Just a nick-pick: enjoyable article, thanks!

Who broke up Maddux and Spahn’s respective runs?

Excellent article. Thank you.

Thanks, Chris!